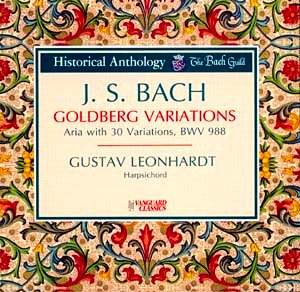

Composer: Johann Sebastian Bach

Composer: Johann Sebastian Bach

Works: Goldberg Variations, BWV 988

Performers: Gustav Leonhardt, harpsichord

Recording: June 1953, Konzerthaus, Vienna

Label: Vanguard OVC 2004

The Goldberg Variations stand as a towering achievement in the Baroque canon, encapsulating Johann Sebastian Bach’s deep understanding of variation form, counterpoint, and keyboard technique. Composed in the early 1740s, it is said to have been commissioned by Count Hermann Karl von Keyserlingk to soothe his insomnia, yet its intricate architecture serves not only as a remedy for sleeplessness but also as an exploration of the human spirit. Gustav Leonhardt’s 1953 recording represents a pivotal moment in the “authentic” performance movement, marking one of the earliest harpsichord renditions that sought to recapture Bach’s intentions in a modern context.

Leonhardt’s interpretation is marked by a youthful boldness that at times verges on inconsistency. The decision to omit repeats in order to fit the entire work onto a single disc may have been practical given the technological limitations of the time, yet it sacrifices the intricate structural balance that these repetitions provide. The opening aria, which typically conveys a serene and reflective character, feels unusually un-Bachish in its slower tempo and lack of the expected gravitas. This initial choice sets a somewhat tentative tone that reverberates throughout the recording. However, as the variations unfold, one discovers moments of lyrical beauty and spirited vitality; for instance, the fifth variation bubbles with a level of energy that is invigorating, while the eighth variation showcases a buoyant playfulness that sheds light on Leonhardt’s interpretive strengths.

Despite the occasional lapses in interpretive coherence, certain slow variations, particularly the introspective 25th, reveal a depth of character and emotional resonance that is commendable. Leonhardt’s use of tempo fluctuations, although at times erratic, does provide a compelling contrast to the faster variations, allowing for a nuanced exploration of the contrasting moods embedded within the work. It is worth noting that his later recordings present a more unified vision, showcasing a matured understanding of Bach’s textural complexities and the idiomatic nature of the harpsichord.

However, the recording quality itself poses a significant challenge to the listener. The harpsichord’s sound is disappointingly tinny and lacks the depth and resonance that modern listeners have come to expect. Much of this can be attributed to the recording practices of the 1950s, but it also reflects the limitations of the instrument used. In comparison to contemporary recordings, such as those by Andreas Staier or Pierre Hantaï, this rendition falls short in achieving a rich and vibrant sound palette that can fully convey the architectural brilliance of Bach’s music.

Acknowledging the historical importance of this recording is essential; it serves as a document of a nascent movement that began to reclaim Bach’s music from the confines of Romantic interpretations. Leonhardt’s pioneering efforts were instrumental in setting the stage for subsequent generations of performers. Yet, while this recording offers a fascinating glimpse into the evolution of Bach interpretation, its technical shortcomings and unevenness in execution ultimately position it more as a collector’s item than an essential listening experience for the casual enthusiast. The spirit of innovation that Leonhardt embodies here is commendable, but it is overshadowed by the limitations of both the performance and the recording technology of the era.