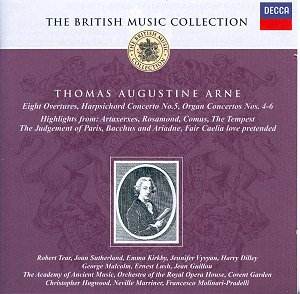

Composer: Thomas Arne

Composer: Thomas Arne

Works: Eight Overtures, Harpsichord Concerto No. 5, Organ Concertos Nos. 4-6, selections from Artaxerxes, Comus, Rosamond, The Tempest, The Judgement of Paris

Performers: The Academy of Ancient Music, Christopher Hogwood; Robert Tear, tenor; The Academy of St Martin-in-the-Fields, Neville Marriner; Joan Sutherland, soprano; George Malcolm, harpsichord; Jean Guillou, organ; Berlin Brandenburg Orchestra, René Klopfenstein

Recording: Various recordings made between 1953 and 1991

Label: Decca

Thomas Arne occupies a unique and somewhat overshadowed position in the pantheon of 18th-century British composers. While George Frideric Handel’s towering presence often eclipsed his contemporaries, Arne’s contributions, particularly as a vocal melodist and dramatist, deserve renewed attention. This compilation from Decca, featuring a broad assortment of Arne’s works, offers a window into the vibrancy of British music during the Georgian era. The collection ranges from the buoyant Eight Overtures to the lyrical Organ Concertos, providing a comprehensive look at Arne’s stylistic breadth and his enduring legacy as a composer of operatic and concert music.

The Eight Overtures, performed by the Academy of Ancient Music under Christopher Hogwood, stand out for their lightness and grace. These overtures serve not only as an introduction to the operas they precede but also as independent concert works. The ensemble’s spirited playing, albeit recorded in 1973, exudes a freshness that echoes the excitement of early period instrument performances. The intonation may present a roughness by today’s standards, but this rawness contributes to the charm, illustrating a time when the period instrument revival was still finding its footing. Each overture reveals Arne’s mastery of orchestration and melodic development, particularly the deft interplay between strings and woodwinds, which Hogwood captures with a deft touch.

Contrastingly, the performances of the keyboard concertos, featuring George Malcolm and Jean Guillou, while proficient, lack the same vibrant character. Malcolm’s harpsichord, though capable, suffers from a tonal flatness that detracts from the intricate dialogue Arne intended between the keyboard and the orchestra. The organ concertos present similar challenges; while Guillou’s technique is impeccable, the overall sound quality feels disconnected from the intended English Baroque aesthetic. The instruments used, though well-played, did not embody the rich, nuanced sound palette that Arne would have envisioned, especially considering his specific orchestral and keyboard writing, which was designed for instruments with distinct tonal qualities.

The vocal selections included here further illustrate Arne’s prowess as a melodist. Joan Sutherland’s rendition of “The Soldier tir’d” from Artaxerxes is a tour de force. While her interpretation may diverge from contemporary performance practices, the sheer power and clarity of her voice elevate the aria to sublime heights. Sutherland’s ability to convey the emotional weight of the text compensates for any perceived ‘un-modern’ elements in the orchestral accompaniment. Robert Tear, recorded in 1969, similarly excels in his vocal performances, demonstrating superb diction and a deep understanding of the lyrical content, though he is somewhat hindered by the orchestral style of the time.

Emma Kirkby’s contributions, while technically proficient, may feel somewhat underwhelming in comparison to the dramatic flair exhibited by Sutherland and Tear. Her interpretations, though earnest, often come across as too delicate for the robust emotional fabric of Arne’s works. The final track featuring Jennifer Vyvyan offers an intriguing glimpse into historical performance practices, but the piano’s role in an orchestral song from the 18th century seems a misguided choice, ultimately detracting from the authenticity of Arne’s intended sound world.

This double disc is a fascinating exploration of Thomas Arne’s output, though it is not without its imperfections. The juxtaposition of various recording styles—from the raw, exhilarating performances of the Academy of Ancient Music to the more polished but less stylistically coherent renditions of the organ and harpsichord concertos—creates a somewhat disjointed listening experience. However, it remains a valuable collection for those seeking to understand the depth and variety of Arne’s contributions to British music. The performances, particularly of the overtures and select arias, offer moments of genuine musical joy and a compelling reminder that Arne, while often overshadowed by Handel, was a significant force in his own right. The collection provides a worthwhile canvas upon which to appreciate the nuances of early British opera and concert music.