Composer: Andreas

Composer: Andreas

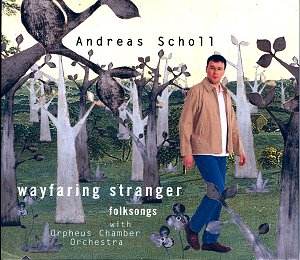

Works: Wayfaring Stranger – Folksongs

Performers: Andreas Scholl, countertenor; Edin Karamazov, lute; Jon Pickow, dulcimer, banjo; Stacey Shames, harp; Orpheus Chamber Orchestra

Recording: Rec: May 2001, Recital Hall, Performing Arts Center, Purchase College, Purchase, New York

Label: DECCA

Andreas Scholl’s “Wayfaring Stranger – Folksongs” presents a collection of traditional melodies drawn from the English, Irish, Scottish, and American folk traditions, showcasing his intent to bridge the classical realm with more populist musical idioms. Emerging at a time when the classical world is increasingly drawn to crossover ventures, this recording seeks to capture the essence of folk music through the lens of Scholl’s renowned countertenor voice, which has previously flourished in the baroque repertoire. Yet, the juxtap of Scholl’s ethereal vocal qualities with the earthy roots of folk music raises questions about authenticity and interpretive alignment.

Interpretively, Scholl’s performance is imbued with a striking purity and emotional resonance. His voice, characterized by a bright, clarion timbre, effortlessly navigates the upper registers, imbuing each phrase with an almost otherworldly lightness. However, this very quality becomes a double-edged sword. While the purity of tone is undeniably appealing, it often seems at odds with the intrinsic gravitas of the folk songs, many of which have narratives steeped in struggle and longing. For instance, in “Wild Mountain Thyme,” one anticipates a robust, earthy delivery that evokes the rugged landscapes of the Scottish Highlands. Instead, Scholl’s interpretation feels more akin to a Broadway rendition, lacking the raw emotional undercurrent that folk music demands.

The ensemble accompanying Scholl—featuring lute, dulcimer, banjo, and harp—contributes a rich tapestry of sound that aims to evoke the pastoral origins of these songs. Edin Karamazov’s lute playing is particularly noteworthy, offering intricate counterpoints that shimmer beneath Scholl’s soaring lines. Yet, even with these varied instrumental textures, the arrangements often feel overly polished, leaning towards a stylized interpretation rather than a genuine folk expression. The dulcimer’s bright, resonant tones in “Barbara Allen,” while technically impeccable, further illustrate this disconnect, sounding more like an ornamentation than an integral part of the narrative.

The recording quality itself is pristine, with a clarity that allows each instrumental voice to shine. The engineering captures the nuances of Scholl’s vocal delivery, though it often accentuates the dissonance between his refined technique and the raw emotionality characteristic of folk traditions. The mix, while well-balanced, leans towards a polished sound that may alienate purists who seek the unvarnished authenticity of traditional folk music.

In terms of comparison, one might look to Alfred Deller, whose own forays into folk music decades ago felt more organically connected to his baritone’s depth and tone. Deller’s interpretations bore the weight of history and narrative, whereas Scholl’s approach risks veering into the realm of commerciality, reminiscent of crossover artists who prioritize marketability over artistic fidelity. This raises a significant question: has Scholl, in his quest for broader appeal, perhaps compromised the very essence of the folk songs he seeks to celebrate?

The collection will likely resonate with listeners who appreciate Scholl’s vocal prowess and the beauty of the arrangements, serving as an accessible introduction to folk music for those uninitiated in the genre. Yet, for dedicated folk enthusiasts or classical purists, this recording may feel like an unsatisfying compromise, where the essence of the music is diluted by a desire for crossover success. Scholl’s artistry shines through, but the choice of repertoire and interpretive lens does not fully honor the rich, often melancholic roots of the material.