Composer: Aga

Composer: Aga

Works: O lieb’, so lang du lieben kannst; Kdyz nine stara matka; Siroke rukavy; Höre lch Zigeunergeigen; Gruss dich Gott, du liebes Nesterl; Es lebt’ eine Wilja; To dawny moj znajorny; Les Berceaux; Les chemins de l’amour; Estrellita; Merce, dilette amiche; Qui la voce sua soave; O mio babbino caro; Si, mi chiamano Mimi; Dien’ li tsarit; Viesiennyie vody

Performers: Aga Winska (soprano), [Piano accompaniment unspecified]

Recording: November 2001

Label: AGW 2002

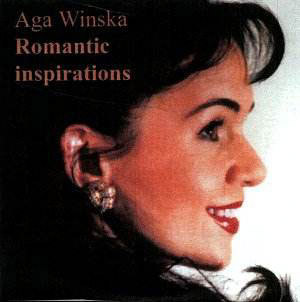

Aga Winska’s latest album, “Romantic Inspirations,” showcases a diverse selection of songs that traverse the rich landscape of the Romantic repertoire, featuring works by composers from Liszt to Rachmaninov. The historical context for these pieces is both broad and deeply rooted in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when emotional expressiveness and lyrical beauty were paramount in the art of song. Winska’s previous recordings, notably her Mozart arias, indicated a promising foundation, and this new release serves as a testament to her evolving artistry.

The album opens with Liszt’s “O lieb’, so lang du lieben kannst,” where Winska’s interpretation reveals a mature understanding of the text’s emotional weight. Her voice has indeed developed since her earlier recordings; however, there remains a tendency to overemphasize certain tonal qualities in an effort to convey intensity. For example, the vibrato, while expressive, occasionally encroaches upon the legato line, leading to moments where the fluidity of the musical phrase is compromised. This is particularly evident in the Vilja Lied from Lehár’s “Die lustige Witwe,” where the lush orchestration of the piano accompaniment underscores Winska’s vocal choices, revealing both the strength and the fragility in her sound.

Winska’s command of the French repertoire, showcased in Fauré’s “Les Berceaux” and Poulenc’s “Les chemins de l’amour,” is commendable. The clarity of her diction and the nuanced phrasing in these pieces highlight her sensitivity to the text. However, it is in these tracks that the recording’s engineering choices become apparent; the microphone captures the piano’s richness admirably, yet it also amplifies the sharper edges of Winska’s tone—an aspect that may distract from the overall lyricism intended in these selections.

The selection of songs from various operas and operettas, including Dvořák’s and Puccini’s arias, demonstrates Winska’s versatility. Yet, one cannot overlook the challenges she faces in balancing technique with the emotional demands of these works. In “O mio babbino caro,” her approach to the climactic moments is earnest, yet the execution sometimes lacks the effortless ease that the aria demands. The timbre can turn slightly harsh, which detracts from the tender yearning that characterizes Lauretta’s plea. Similarly, in Tchaikovsky’s “Dien’ li tsarit,” while the dramatic intentions are clear, the execution lacks the vocal warmth that would transform the piece from mere performance to heartfelt expression.

Despite the occasional discrepancies in tonal control, Winska’s commitment to the original languages of her repertoire is commendable, allowing for an authentic connection with the material. The inclusion of Cyrillic text for Russian songs enhances this authenticity, inviting listeners to engage with the lyrical depth of these works in their original forms.

The culmination of Winska’s journey on this recording reflects a promising yet uneven exploration of a repertoire deeply embedded in the Romantic tradition. While there are undeniable strengths in her vocal agility and interpretative choices, there remains a need for further refinement in vocal technique and a return to the purity of sound that first captured listeners’ attention. With time and continued exploration, Winska has the potential to fully realize her artistic voice, bridging the gap between her ambitious aspirations and the technical mastery required to express them.