Composer: Antonín Dvořák

Composer: Antonín Dvořák

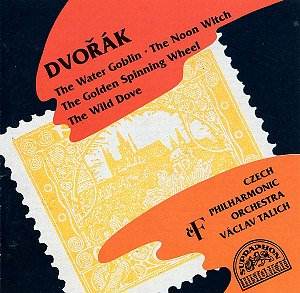

Works: The Water Goblin, op. 107; The Noon Witch, op. 108; The Golden Spinning Wheel, op. 109; The Wild Dove, op. 110

Performers: Czech Philharmonic Orchestra/Václav Talich

Recording: Recorded at the Domovina Studio, Prague, 14th July 1949 (1), The Dvořák Hall of Rudolfinum, Prague, 4th April 1951 (2), 20th March 1951 (3), 2nd and 3rd April 1951 (4)

Label: SUPRAPHON

Antonín Dvořák’s symphonic poems, steeped in Czech folklore and myth, stand as vibrant exemplars of late Romanticism and a testament to the composer’s ability to weave narrative into orchestral fabric. The recordings by Václav Talich with the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra capture the essence of Dvořák’s imaginative world, offering a profound exploration of these lesser-known works that often languish in the shadow of his more celebrated symphonies and concertos. The historical significance of these pieces is underscored by their rich orchestration and the emotional depth that Dvořák imbues into his portrayal of folk tales.

Talich’s interpretation of The Water Goblin showcases the conductor’s symphonic prowess, allowing the music to unfold organically. Each section flows into the next, creating a cohesive musical narrative that highlights Dvořák’s structural clarity. The recording from 1949 may reveal some age, with a slightly hoarse quality, yet it brings an authenticity reflective of the time. This contrasts with Zdeněk Chalabala’s more operatic approach, which, while vividly characterizing each moment, sometimes sacrifices the overarching structural integrity that Talich maintains. The opening’s buoyant energy gives way to a hauntingly atmospheric depiction of the underwater kingdom, where Talich’s keen sense of pacing allows for an immersive experience—particularly in the climactic moments where the themes collide.

The Noon Witch presents an interesting dichotomy in interpretation. Talich’s reading, while structurally coherent, sometimes feels less impassioned, particularly in the latter sections where the musical argument falters. Chalabala’s portrayal, however, infuses the piece with a vividness that captivates the listener, especially in the way he characterizes the individual moments of the story. This is particularly noteworthy in the climactic scenes, where Chalabala’s expressive tempo fluctuations breathe life into the narrative, creating a contrast to Talich’s more straightforward, symphonic execution. The sound quality in the later recordings (1951) is notably better, allowing for a more nuanced appreciation of the orchestra’s vibrant colors.

In The Golden Spinning Wheel, both conductors find a suitable balance between lyrical beauty and rhythmic vitality. Talich’s sensitivity to timbre shines through in the lush orchestral passages, particularly at 2’03”, where the strings’ delicate intertwining with the woodwinds creates a moment of sheer enchantment. Chalabala, on the other hand, emphasizes the lyrical ardor present in the thematic material, skillfully revealing the emotional undercurrents that pulse beneath the surface. This duality in approach—Talich as the architect and Chalabala as the storyteller—offers a rich listening experience, showcasing the multifaceted nature of Dvořák’s music.

The Wild Dove emerges as the crowning jewel of these symphonic poems. Here, Talich’s command of the orchestral palette is evident; he navigates the sweeping lines and mournful themes with an incisive clarity that underscores the piece’s emotional weight. The central section radiates an incandescent beauty, a testament to Talich’s interpretive depth. While Chalabala’s interpretation may come across as more homespun, his attention to detail in the final sections enhances the poignancy of the dove’s song, skillfully intertwining the thematic material with the orchestral color.

The recordings encapsulate the unique sound of the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra during this period, characterized by vibrant strings and piquant winds that are integral to Dvořák’s orchestral language. This historical aspect enhances the listening experience, as the performances resonate with the cultural heritage of Czech music. While modern interpretations by conductors like Rafael Kubelík or Neeme Järvi may offer more polished soundscapes, the charm of Talich’s recordings lies in their raw authenticity and historical significance.

Talich’s interpretations, while occasionally overshadowed by the more exuberant readings of Chalabala, reveal a conductor deeply attuned to the subtleties of Dvořák’s orchestral writing. The interplay between the two conductors illustrates a rich tapestry of interpretation, where each brings distinct qualities to Dvořák’s evocative stories. Collectively, these recordings serve not only as a celebration of Dvořák’s symphonic poems but also as a valuable window into the interpretive practices of mid-20th-century Czech conducting.