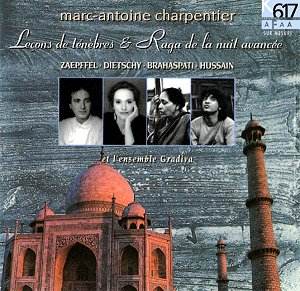

Composer: Marc-Antoine Charpentier

Composer: Marc-Antoine Charpentier

Works: Leçons de ténèbres, Raga de la nuit avancée

Performers: Sulochana Brahaspati (voice), Véronique Dietschy (soprano), Alain Zaepffel (counter-tenor), Ensemble Gradiva

Recording: Made in the church of St-Jean de Grenelle, September 1991

Label: K617

The music of Marc-Antoine Charpentier, a pivotal figure in the French Baroque, is often celebrated for its dramatic depth and intricate vocal lines, particularly in his sacred works. The “Leçons de ténèbres,” composed for Holy Week, exemplifies this with their poignant settings of the Lamentations of Jeremiah, characterized by a profound exploration of grief and reflection. This recording intriguingly juxtaposes these works with Northern Indian classical music, specifically the raga tradition, under the overarching thematic banner of night. The rationale presented in the booklet claims that both musical forms engage in a meditative exploration of emotion, yet this premise raises significant questions about the effectiveness of such a pairing.

The performances of the “Leçons de ténèbres” are marked by a certain elegance, particularly in the expressively nuanced interpretations by Dietschy and Zaepffel. However, the vocal execution lacks the full-bodied richness that Charpentier’s melodic lines demand. Dietschy’s soprano, while agile, occasionally sounds thin, detracting from the opulent textures that characterize Baroque choral music. In contrast, the raga “Raga de la Minuit,” performed by Sulochana Brahaspati, presents a compelling contrast, showcasing a powerful and emotive delivery that fully exploits the raga’s intricate ornamentation and rhythmic flexibility. The tabla accompaniment, while integral to the North Indian tradition, introduces a rhythmic tension when placed alongside the flowing phrases of the French repertoire, as both idioms adhere to fundamentally different rhythmic principles.

The engineering and sound quality of the recording merit attention as well. The acoustics of the church of St-Jean de Grenelle contribute a reverberant warmth that enhances the vocal lines, yet the abrupt transitions between the tenebrae and the raga disrupt the listening experience. The shifts lack preparation, resulting in a jarring juxtaposition that undermines the contemplative intent behind both musical forms. This is particularly evident in the fusion of the tabla within the tenebrae, an ill-conceived pairing that fails to reconcile the contrasting rhythmic functions—one striving for momentum while the other seeks to elongate and shape melodic phrases.

Charpentier’s works are traditionally performed over the course of Holy Week, each leçon embodying a distinct emotional arc. The decision to splice these pieces together without their intervening sections compromises their inherent structure, distorting their liturgical context. The booklet’s claim of creating a “single great night raga” is misguided; these sacred texts are designed to stand alone, each conveying a specific narrative and emotional landscape that becomes obscured in this format.

The endeavor to amalgamate Charpentier’s sacred music with the North Indian raga tradition, while ambitious, ultimately falters due to its execution. Each musical tradition possesses a unique emotional and structural integrity that cannot simply be layered upon one another without due consideration of their distinct characteristics. A separate recording for each would have provided a more fruitful exploration of their respective depths, allowing listeners to engage with the rich tapestry of each tradition on its own terms. The intent may have been to create a novel listening experience, but the result is an awkward and unsatisfying compilation that does not do justice to either musical heritage.