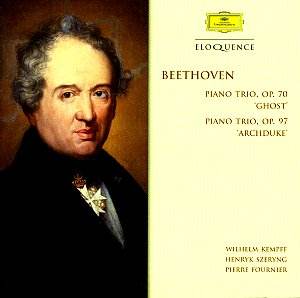

Composer: Ludwig van Beethoven

Composer: Ludwig van Beethoven

Works: Piano Trio in D major Op. 70 “Ghost”, Piano Trio in B flat major Op. 97 “Archduke”

Performers: Wilhelm Kempff, piano; Henryk Szeryng, violin; Pierre Fournier, cello

Recording: 1970

Label: Deutsche Grammophon Eloquence 463 238-2 [71.04]

Beethoven’s piano trios represent a pivotal contribution to the chamber music repertoire, with the “Ghost” and “Archduke” trios standing as two of his most significant achievements. Composed during a time when Beethoven was grappling with his encroaching deafness, these works are infused with a unique blend of emotional depth and structural innovation. The “Ghost” trio, with its spectral qualities, particularly in the Largo assai, and the grandiosity of the “Archduke,” showcase Beethoven’s ability to fuse the intimate with the monumental. This recording by Wilhelm Kempff, Henryk Szeryng, and Pierre Fournier, made in 1970, provides a valuable perspective on these masterpieces, albeit with a few interpretive shortcomings.

The “Ghost” trio opens with a commanding presence, characterized by Kempff’s incisive piano accents and the strings’ lyrical response. Szeryng’s vibrato, normally a hallmark of his expressive playing, occasionally veers into an uncontrolled territory here, which detracts from the overall coherence. Yet, the ensemble achieves a commendable unity, especially in the poignant transitions of the first movement. The “Largo assai” emerges as the performance’s zenith, with Szeryng and Fournier’s phrasing capturing the ethereal essence of Beethoven’s vision. Their careful delineation of the spectral wanderings, as noted by sleeve annotator Carl Rosman, creates a haunting atmosphere that resonates powerfully. The finale bursts forth with infectious energy, highlighting the trio’s technical prowess and interpretive synergy.

However, the “Archduke” trio presents a more mixed experience. While the technical execution is undeniably polished, the first movement suffers from a lack of dramatic impetus. The players seem to engage in a rather subdued exchange, which contrasts starkly with the movement’s inherent vigor. Kempff’s touch, though rich, occasionally leans towards a laissez-faire attitude, leading to muted responses and a general sense of disengagement that undermines Beethoven’s dynamic contrasts. The slow movement, while beautifully crafted, falters under excessive refinement, with Fournier’s staccato passages coming across as overly mannered, creating an artificiality that distances the listener from the emotional core of the music.

The finale’s deliberate tempo, while adhering to Beethoven’s moderato marking, sacrifices the necessary motoric drive. Kempff’s fortissimos at times border on the splashy, leading to a ponderousness that contradicts the movement’s spirited intentions. This lack of incisiveness is particularly evident when juxtaposed with the vibrant interplay found in recordings by Kogan, Rostropovich, and Gilels, where the music’s rhetorical flourishes and harmonic intricacies are more vividly articulated. The ending feels anticlimactic, lacking the triumphant resolution that the “Archduke” demands.

This recording yields a strong performance of the “Ghost” trio, marked by moments of profound connection and interpretive insight. The “Archduke,” however, while technically adept, leaves much to be desired in terms of interpretive depth and dramatic engagement. The sound quality of the recording is commendable, capturing the warmth of the instruments and the nuances of the performance, yet it is the interpretive choices that ultimately define this disc. Cautious recommendation for the “Ghost” trio, tempered by reservations regarding the “Archduke.”