Beethoven’s Op. 29: The Overlooked Quintet That Bridges Genius and Legacy

You know, it’s a damn shame how Beethoven’s Op. 29 String Quintet gets the cold shoulder. This piece plays a pivotal role in connecting the dots between his early and middle works, yet it’s still wallowing in obscurity. It’s like a hidden gem that no one wants to polish.

You know, it’s a damn shame how Beethoven’s Op. 29 String Quintet gets the cold shoulder. This piece plays a pivotal role in connecting the dots between his early and middle works, yet it’s still wallowing in obscurity. It’s like a hidden gem that no one wants to polish.

Beethoven really solidified his reputation in chamber music with his string quartets, setting himself apart from Mozart, who was more into string quintets. And let’s not overlook the audacity in his choice to swap a second cello for a second viola in the quartet. That’s Beethoven for you—always ready to break the mold and show up Mozart and Schubert.

Now, let’s talk about the love letter to Count Moritz von Fries—two masterpieces bearing his mark: this Quintet and the Seventh Symphony. But here’s the kicker—the Quintet’s debut was stifled by some nasty contractual squabbles between publishers. This delayed its release, robbing audiences of a truly remarkable experience. It’s like the universe conspired to keep this brilliance under wraps.

The bias of the composer toward Breitkopf and the dedicatee toward a rival only made matters worse. It’s as if this conundrum has left a stain on the music that lingers even today. But when you listen to Beethoven’s Quintet, it’s clear that this work showcases his artistic genius in a dazzling way—combining boldness with inventiveness.

Take the first movement, for instance. That intricate second subject in A major? It’s a real ear-catcher, masterfully utilizing modulation to draw you in. And the second movement? The distinctive sonata form, coupled with captivating rhythms, proves Beethoven was operating on a different plane of musical genius.

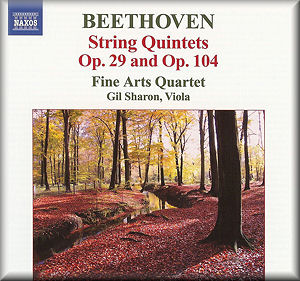

Then there’s the finale, aptly nicknamed “The Storm.” With its brisk tempo and demanding note values, it’s a challenge even for seasoned musicians. Yet, the Fine Arts Quartet, led by Gil Sharon, dives into this deceptively simple piece from 1818 with fearless abandon.

The recording quality brings out a sensitivity in sound that highlights the meticulous part writing. It’s a beautiful balance where the listener really feels the synergy of the ensemble. And speaking of recordings, the Naxos release is a no-brainer for anyone looking to own the definitive version of this Quintet. Great price, impressive performances by Quatuor Ysaÿe and Shuli Waterman—it’s got everything a music lover could want.

In his later years, Beethoven circled back to the quintet format, delivering another masterpiece with Op. 104 while simultaneously crafting the monumental Op. 106 Hammerklavier Sonata. After a creative lull, spurred on by his familial troubles with nephew Karl, he unleashed that musical genius once more in 1818.

Then there’s Brahms, who revisits the quintet medium in Op. 104, showcasing his growth since his early Piano Trio. It’s fascinating to hear how he reinterprets his earlier work, adding layers of intrigue to the listening experience. And let’s not forget the Fine Arts ensemble’s stunning rendition of that little Fugue in D major—a proofing exercise turned into a showcase of their talent.

So here’s the bottom line: Beethoven’s Quintet is a treasure that deserves our attention, and it’s about time we start giving it the recognition it rightfully deserves.