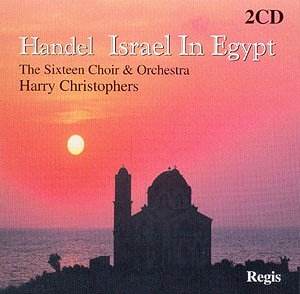

Composer: Georg Friedrich Handel

Composer: Georg Friedrich Handel

Works: Israel in Egypt, Organ Concerto in F, HWV 295

Performers: Nicola Jenkin (soprano), Sally Dunkley (soprano), Caroline Trevor (alto), Neil MacKenzie (tenor), Robert Evans (bass), Simon Birchall (bass), Paul Nicholson (organ), Choir and Orchestra of The Sixteen, Harry Christophers (conductor)

Recording: St Judes on the Hill, 1993

Label: REGIS RRC 2012

Handel’s Israel in Egypt, composed in 1738, offers a compelling tapestry of biblical narrative through an intricate web of choral writing and vivid musical imagery. Intended for the dual appeal of Christian and Jewish audiences alike, this oratorio was not immediately successful, largely due to its unconventional structure, dominated by a substantial choral presence and minimal solo arias. The work’s solemnity and depth, particularly evident in its opening movement, marked Largo assai, sets forth an austere atmosphere that challenges conventional expectations of oratorio form. The music unfolds with a gravitas that reflects Handel’s own reflections on the human condition, notably encapsulating the Israelites’ plight with a profound sense of empathy and gravity.

The performance by The Sixteen, under Harry Christophers’ direction, captures the essence of Handel’s choral mastery. The choir’s ability to convey both the weight of the text and the intricate harmonic structures is commendable, particularly in the dense, counterpoint-laden choruses that populate the work. The balance between sections is meticulously maintained, allowing the voices to resonate with clarity while maintaining a collective intensity that is essential to the narrative’s progression. Christophers’ interpretative choices emerge as particularly effective; he navigates the textural contrasts with a sensitivity that enhances the dramatic arcs within the score. For instance, the transition from the weighty affirmations of despair to the jubilant proclamations of divine intervention is executed with a palpable tension that highlights Handel’s dramatic intent.

The inclusion of the Organ Concerto in F, HWV 295 as an interlude offers a refreshing respite and allows for a juxtaposition of solo and ensemble textures. Paul Nicholson’s performance on the organ is noteworthy for its nuanced articulation and restrained dynamics, which complement the choral work perfectly. The final movement, marked Adagio (ad libitum), presents a delicate, almost improvisational quality that serves as an atmospheric bridge between the two major parts of the oratorio. This interlude, while perhaps not essential to the narrative, enriches the listening experience, providing a moment of introspection before the continuation of the choral drama.

The recording itself is a testament to high-quality engineering standards, capturing the clarity of the choir and the organ with precision. The acoustic space of St Judes on the Hill contributes significantly to the sound, allowing the choir’s blend to flourish without sacrificing the individual clarity of the voices. This aspect is particularly pronounced in the intricacies of Handel’s counterpoint, where the interplay of voices can be distinctly appreciated without muddiness or distortion.

While Israel in Egypt may not cater to the preferences of those averse to choral works, this recording stands as a formidable interpretation of Handel’s vision. The combination of The Sixteen’s virtuosity and Christophers’ insightful direction brings forth a performance that is both engaging and intellectually stimulating. This rendition may well serve as a definitive introduction for modern audiences to the depth and complexity of Handel’s choral writing, capturing the essence of a work that, while historically underappreciated, reveals its profound beauty and significance through careful and passionate interpretation. The artistic synergy of the performers and the thoughtful programming make this recording a valuable addition to the Handel discography.