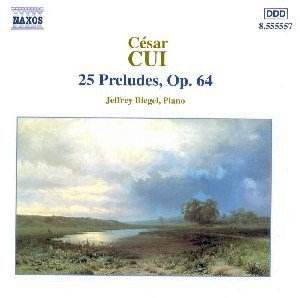

Composer: César Cui

Composer: César Cui

Works: 25 Preludes for Piano Op. 64

Performers: Jeffrey Biegel, piano

Recording: Arum Hall, Valparaiso, Indiana, USA, 16th – 18th September 1992 (Re-issue of Marco Polo 8.223496 1993)

Label: NAXOS 8.555557

César Cui, often overshadowed by his contemporaries in the Russian compositional landscape, notably the “Mighty Handful,” presents a unique voice in his 25 Preludes for Piano, Op. 64. These works, composed during a time when the Prelude was a favored form among Russian composers, reflect a duality of nostalgia and technical simplicity. Cui’s oeuvre, marked by a tendency towards the intimate, diverges from the grand narratives typical of his more renowned peers such as Rachmaninov and Scriabin. Instead, Cui’s Preludes invite a more personal engagement, resonating with the quieter tones of salon music rather than the more explosive concert hall repertoire.

Jeffrey Biegel’s interpretation of these preludes is marked by a nuanced sensitivity that brings out the subtleties of Cui’s writing. The performance is imbued with a lyrical quality that aligns well with the romantic nature of the pieces. Notably, Biegel’s careful attention to phrasing allows the delicate melodic lines to emerge clearly, particularly in the quieter preludes where a sense of introspection is paramount. The first prelude in C major, for instance, is delivered with a crystalline clarity that showcases its harmonic simplicity while infusing it with emotional depth. This approach is particularly effective in the more reflective pieces such as the seventh prelude in B minor, where Biegel captures the wistfulness embedded in the music.

The recording quality, however, presents a dichotomy. While the piano’s timbre is generally pleasing, there is an occasional brittle quality to the sound that detracts from the overall warmth of the performance. Some of the more vigorous passages risk losing their punch, sounding almost constricted as if the piano were ensconced in a tight space. This is particularly evident in the lively waltzes and marches that punctuate the collection. A comparison with other recordings, such as those by Boris Berezovsky or the earlier Marco Polo release, reveals that while Biegel’s interpretation shines in its lyrical moments, it sometimes lacks the full-bodied resonance found in these other renditions.

Cui’s Preludes, while not groundbreaking in their harmonic exploration compared to the likes of Chopin or Scriabin, possess their own charm through their unique key relationships and thematic continuity. Each prelude transitions fluidly into the next, often juxtaposing major keys with their mediant minors, a thoughtful decision that provides a cohesive listening experience. This cycle is not merely a collection of standalone pieces; rather, it is a tapestry woven together by Cui’s melodic sensibilities and harmonic choices.

The 25 Preludes for Piano stand as a testament to Cui’s ability to create music that, while technically less demanding, speaks to a more intimate and personal space. Biegel’s performance, filled with sensitivity and finesse, captures the essence of these miniatures, breathing life into Cui’s world of whispered dreams and gentle reminiscences. While they may not reach the heights of their more celebrated counterparts, these preludes deserve recognition and regular performance. Cui may not be a household name in the pantheon of classical music, but through these Preludes, he offers a refreshing perspective on the Romantic piano repertoire that warrants our attention and appreciation.