Composer: Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849)

Composer: Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849)

Works: Scherzo no. 3 in C sharp minor, op. 39; Boléro in A minor, op. 19; Nocturne no. 18 in E, op. 62/2; Ballade no. 1 in G minor, op. 23; Mazurka in B minor, op. 33/4; Polonaise-Fantaisie in A flat, op. 61; Mazurka in A minor, op. 17/4; Ballade no. 3 in A flat, op. 47; Scherzo no. 2 in B flat minor, op. 31; Ballade no. 4 in F minor, op. 52; Valse in E flat, op. 18; Scherzo no. 1 in B minor, op. 20; Nocturne in B, op. 62/1; Polonaise in C sharp minor, op. 26/1; Mazurka in C minor, op. 56/3; Ballade no. 2 in F, op. 38; Nocturne in E flat, op. 9/2; Sonata no. 2 in B flat minor, op. 35; Impromptu no. 1 in A flat, op. 29; Lento con gran espressione in C sharp minor, op. posth; Nocturne in F sharp minor, op. 48/2; Waltz in E flat, op. posth; Impromptu in F sharp, op. 36; Marche funèbre in C minor, op. posth; 3 Mazurkas, op. 50; Polonaise in A flat, op. 53; 24 Preludes, op. 28; Valse in A flat, op. 34/1; 3 Mazurkas, op. 59; Nocturne in D flat, op. 27/2; Valse in F, op. 34/3; Barcarolle in F sharp, op. 60

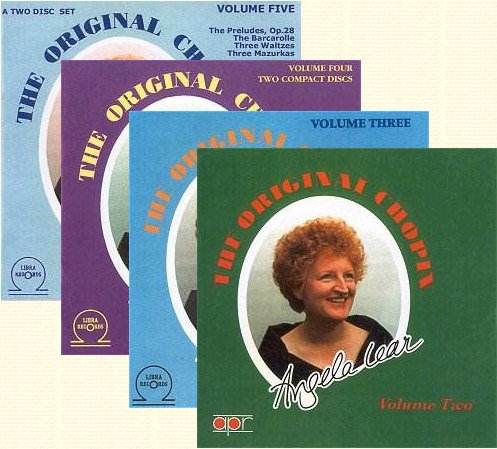

Performers: Angela Lear (pianoforte)

Recording: Recorded 27th July 1994, 22nd May 1995, 22nd May 1996, and 4th November 1996, St. George’s, Brandon Hill, Bristol, and Royal Academy of Music

Label: Libra Records

The enduring allure of Chopin’s oeuvre is rooted in its rich emotional tapestry and intricate technical demands, making it a perennial favorite among pianists and audiences alike. Angela Lear’s ambitious five-volume project, “The Original Chopin,” seeks to peel back the layers of interpretative tradition that have enveloped these works, positing itself as a restoration of Chopin’s authentic intentions. This endeavor is both noble and fraught with the inherent challenges of reconciling historical fidelity with artistic expression.

In her performances, Lear approaches the repertoire with a clear sense of reverence for the score, often eschewing the flamboyant liberties taken by some of her illustrious predecessors. For instance, in the Scherzo no. 3, she adheres closely to the score’s tempo markings, yet one might argue that this fidelity sometimes comes at the expense of the piece’s inherent dramatic flair. While Rubinstein’s famed recording captures a more explosive character, Lear’s interpretation—though technically sound—lacks the visceral excitement that can elevate the music beyond mere notes. Her playing, while competent, occasionally feels restrained, particularly in pieces like the G minor Ballade, where the emotional climaxes do not resonate as powerfully as they might under the hands of a more theatrical artist.

Technical execution in Lear’s recordings is undeniably proficient; her command over the piano allows her to navigate the intricate passages of the Boléro and the Nocturnes with clarity. However, one crucial aspect where her interpretations diverge from the more celebrated recordings lies in the subtleties of phrasing and touch. For example, in the E major Nocturne, her melodic line does not sing with the requisite lyricism. This contrasts starkly with Rubinstein’s interpretation, where the voice-leading is imbued with a warmth that invites the listener into an intimate dialogue. The result is a performance that, while scrupulous in its adherence to the score, sometimes feels more like a musical lecture than an impassioned conversation.

Recording quality across the five volumes remains consistent, capturing the nuanced dynamics of Lear’s playing well, though at times the acoustics can feel a touch too clinical, lacking the warmth and resonance that a more vibrant venue might afford. The engineering is clear, allowing the listener to appreciate the intricacies of Lear’s touch, but it does not always convey the emotional depth that is often the hallmark of great Chopin performances.

The fifth volume marks a notable improvement, revealing Lear’s growing confidence and interpretative maturity. The Preludes, particularly, benefit from her more spontaneous approach, allowing the music’s character to emerge more vividly. However, even in this volume, Lear’s insistence on a strict adherence to Chopin’s text raises questions about the balance between fidelity to the score and the necessity of interpretative license. While her performances are commendable for their technical accuracy, they sometimes lack the interpretative flair that has defined the best recordings of Chopin’s music.

Angela Lear’s exploration of Chopin is an earnest contribution to the ongoing discourse on how best to perform this ever-challenging repertoire. The series as a whole presents a mixed bag; while her later volumes show promise and growth, the earlier recordings reveal a pianist still grappling with the balance between textual fidelity and expressive interpretation. It is in the later volumes, particularly the fifth, that Lear begins to carve out her own interpretative voice, suggesting that the journey towards understanding the delicate interplay of Chopin’s music is one she continues to navigate. The series undoubtedly merits consideration for those interested in a scholarly approach to Chopin’s works, even if it does not yet consistently reach the interpretative heights achieved by the greats of the piano.