Early Life and Musical Foundations

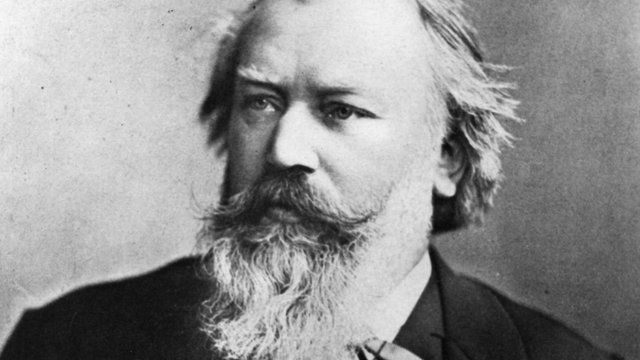

Johannes Brahms, born on May 7, 1833, in Hamburg, Germany, is celebrated as one of the leading composers of the Romantic era, revered for his ability to combine the emotional depth of Romanticism with the structural rigor of Classical forms. His music, characterized by rich harmonic language, intricate counterpoint, and profound emotional expression, reflects a deep reverence for the musical traditions of the past while also exploring new expressive possibilities. Brahms’s life and work are often seen as a bridge between the classical style of Beethoven and the more expansive, emotional language of later Romantic composers.

Johannes Brahms, born on May 7, 1833, in Hamburg, Germany, is celebrated as one of the leading composers of the Romantic era, revered for his ability to combine the emotional depth of Romanticism with the structural rigor of Classical forms. His music, characterized by rich harmonic language, intricate counterpoint, and profound emotional expression, reflects a deep reverence for the musical traditions of the past while also exploring new expressive possibilities. Brahms’s life and work are often seen as a bridge between the classical style of Beethoven and the more expansive, emotional language of later Romantic composers.

Brahms’s early life was marked by modest beginnings. His father, Johann Jakob Brahms, was a musician who played several instruments, and his mother, Johanna Nissen, was a seamstress. From an early age, Brahms was exposed to music, receiving his first piano lessons from his father. He quickly demonstrated prodigious talent, and by the age of seven, he was already performing in public. Despite the family’s financial struggles, Brahms’s parents recognized his potential and supported his musical education. He studied piano with Otto Friedrich Willibald Cossel and later with Eduard Marxsen, a respected pianist and composer who introduced Brahms to the works of Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven.

As a teenager, Brahms began to make a name for himself as a pianist, performing in local venues and earning a living by playing in taverns and providing piano lessons. It was during this period that he began to compose in earnest, although many of his early works were destroyed by the self-critical young composer. His big break came in 1853 when he met the violinist Joseph Joachim, who recognized Brahms’s talent and introduced him to Robert and Clara Schumann. The Schumanns were deeply impressed by Brahms’s music, particularly his piano compositions, and Robert Schumann famously hailed him as the future of German music in an article titled “Neue Bahnen” (New Paths). This endorsement launched Brahms’s career and established him as a rising star in the musical world.

Brahms and the Symphony: A Long-Awaited Masterpiece

One of the most remarkable aspects of Johannes Brahms’s career was his cautious approach to composing symphonies. In an era dominated by the towering legacy of Beethoven, Brahms felt the weight of expectation keenly, and he hesitated to present himself as a symphonist until he was certain he could meet the high standards set by his predecessor. As a result, he did not complete his *Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68* until 1876, when he was 43 years old, despite having begun sketches for it two decades earlier.

Brahms’s *Symphony No. 1* was immediately recognized as a significant achievement, often referred to as “Beethoven’s Tenth” due to its monumental character and its clear connections to Beethoven’s symphonic language. The symphony is marked by its dramatic intensity, structural clarity, and the masterful integration of thematic material. The finale, in particular, with its noble, hymn-like theme, has often been compared to the “Ode to Joy” from Beethoven’s *Ninth Symphony*. However, Brahms’s symphony is no mere imitation; it represents his personal synthesis of Classical tradition and Romantic expressiveness, establishing him as a worthy successor to Beethoven.

Following the success of his first symphony, Brahms went on to compose three more symphonies, each of which showcases a different aspect of his compositional genius. His *Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 73* (1877) is more pastoral and lyrical, often described as his “Pastoral Symphony” due to its serene character and the warmth of its melodies. The *Symphony No. 3 in F major, Op. 90* (1883) is noted for its autumnal tone and complex interplay of themes, particularly the famous *Allegro con brio*, which features a motto motif derived from the notes F-A-F, symbolizing Brahms’s personal motto “Frei aber froh” (“Free but happy”). His final *Symphony No. 4 in E minor, Op. 98* (1885) is perhaps his most profound, with its rigorous structure, culminating in a chaconne—a set of variations on a repeating bass line—demonstrating Brahms’s deep understanding of Baroque forms.

Chamber Music and the Piano: Intimacy and Innovation

In addition to his symphonies, Johannes Brahms made significant contributions to the chamber music repertoire, producing some of the most enduring and beloved works in this genre. Brahms’s chamber music is characterized by its intimate expression, sophisticated interplay of voices, and a deep sense of musical conversation between instruments. His early works, such as the *Piano Quintet in F minor, Op. 34* (1864) and the *String Sextet No. 1 in B-flat major, Op. 18* (1860), demonstrate his mastery of form and his ability to balance lyricism with structural rigor.

Brahms’s later chamber works, including the *Clarinet Quintet in B minor, Op. 115* (1891) and the *Piano Trio No. 3 in C minor, Op. 101* (1886), are marked by a deep introspection and a mature, often autumnal quality. The clarinet quintet, in particular, is a masterpiece of late Romantic chamber music, with its haunting melodies and subtle interplay between the clarinet and the strings. It was written for the clarinetist Richard Mühlfeld, whose playing deeply inspired Brahms during the last years of his life.

As a pianist, Brahms also left a substantial body of work for the piano, ranging from the early virtuoso compositions such as the *Piano Sonata No. 3 in F minor, Op. 5* (1853) to the introspective late piano pieces, the *Klavierstücke, Op. 116–119* (1892–1893). These late piano works, often considered among his finest compositions, are miniature masterpieces that explore a wide range of emotions, from the lyrical and tender to the dark and brooding. They reflect Brahms’s deep engagement with the piano as an instrument capable of expressing the most profound and intimate thoughts.

A German Requiem: Brahms’s Spiritual Testament

One of Brahms’s most significant and personal works is *Ein deutsches Requiem, Op. 45* (*A German Requiem*), completed in 1868. Unlike the traditional Latin Requiem Mass, which focuses on the souls of the dead, Brahms’s *Requiem* is a non-liturgical work that offers comfort to the living. The text, selected by Brahms from the Lutheran Bible, reflects themes of human mortality, hope, and consolation. This choice of text and the work’s overall tone are often thought to have been inspired by the deaths of Brahms’s mother and his mentor, Robert Schumann.

*Ein deutsches Requiem* is composed in seven movements, each of which deals with different aspects of the human experience in the face of death. The first movement, “Selig sind, die da Leid tragen” (“Blessed are they that mourn”), sets the tone of solace and reassurance that permeates the entire work. The central movement, “Wie lieblich sind deine Wohnungen” (“How lovely are thy dwellings”), is a serene and uplifting meditation on the peace of the afterlife. The final movement, “Selig sind die Toten” (“Blessed are the dead”), brings the work to a gentle, transcendent conclusion.

The *Requiem* was a monumental success and established Brahms as a composer of international stature. Its deep spirituality, combined with its masterful orchestration and choral writing, has made it one of the most enduring choral works in the Western classical canon. Unlike the dramatic requiems of composers like Verdi, Brahms’s *Requiem* is contemplative and inward-looking, offering solace rather than fear, making it a deeply humanistic work that resonates with audiences of all backgrounds.

Legacy and Influence

Johannes Brahms’s legacy is one of profound impact on the world of classical music. He is often regarded as the last great composer in the lineage of Beethoven, upholding and expanding the classical traditions while also embracing the expressive possibilities of the Romantic era. His music is celebrated for its perfect balance of form and emotion, its intellectual depth, and its rich harmonic language.

Brahms was highly respected by his contemporaries, including Antonín Dvořák, who was significantly influenced by Brahms’s style and mentorship. His music has had a lasting influence on composers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including Gustav Mahler and Arnold Schoenberg. Schoenberg, despite his move towards atonality, admired Brahms’s use of developing variation—a technique in which a musical idea is continuously evolved—which Schoenberg considered a precursor to his own compositional methods.

Brahms’s adherence to classical forms in an era when many composers were embracing programmatic and nationalistic music has led to his being seen as a somewhat conservative figure. However, this view overlooks the innovative ways in which he expanded the possibilities of these forms, particularly in his use of rhythm, counterpoint, and harmonic complexity.

Beyond his technical achievements, Brahms’s music is cherished for its emotional depth and humanity. Whether in the grandeur of his symphonies, the intimacy of his chamber music, or the spiritual depth of his *Requiem*, Brahms’s work speaks to the universal experiences of love, loss, hope, and joy. His music remains a cornerstone of the classical repertoire, beloved by performers and audiences alike for its profound beauty and enduring emotional power