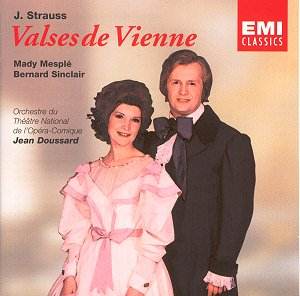

Composer: Johann Strauss (1801-1849) & Son (1825-1899)

Composer: Johann Strauss (1801-1849) & Son (1825-1899)

Works: Valses de Vienne

Performers: Mady Mesplé, Bernard Sinclair, Christiane Stutzmann, Arta Verlen, Philippe Guadin, Jaques Loreau, Pierre Saugey; René Duclos Choirs, Orchestra of National Theatre of Opera Comique/Jean Doussard

Recording: 1972, Salle Wagram, Paris, France

Label: EMI

Johann Strauss I and II are synonymous with the golden age of Viennese waltzes, their works embodying a spirit of festivity and elegance that captured the cultural zeitgeist of 19th-century Europe. The “Valses de Vienne,” arranged by Erich Wolfgang Korngold in 1930, seeks to encapsulate this nostalgia through a pastiche of their most beloved melodies, intended for a time when the populace craved escapism following the upheaval of the stock market crash. This recording serves as a testament to the Strauss legacy, weaving together a tapestry of familiar tunes that evoke the grandeur of Vienna while simultaneously offering a French operetta experience.

The performance, led by conductor Jean Doussard, is marked by a buoyant tempo that effectively conveys the exuberance inherent in Strauss’s music. The orchestra of the National Theatre of Opera Comique exhibits a commendable balance between the lush string sections and the spirited woodwinds, breathing life into the waltzes. However, the recording suffers from a notable lack of detail due to distant mic placement, which diminishes the expected clarity of intricate passages. For instance, the pizzicato segment (CD1 tk21), which showcases a modern sensibility, loses some of its playful character in the muddled soundscape. The interpretation of the Radetzky March, which opens the performance, adopts a brisk and celebratory approach, yet the subsequent transition to vocal numbers lacks sufficient clarity, leaving the listener grappling to identify the original melodies interspersed throughout.

The soloists, including the luminous Mady Mesplé and the robust Bernard Sinclair, bring a distinctive Viennese flavor to the chorus numbers. Their vocal techniques, while commendable in blending with the orchestral backdrop, are occasionally overshadowed by the recording’s sonic limitations, leading to a lack of articulation that detracts from their performances. The diction, a crucial element of operatic delivery, suffers here, not necessarily from the singers’ abilities but rather from the engineering choices that obscure the text. The engaging pace set by Doussard does help sustain interest, particularly during moments of heightened drama, like the musical box effect in Act III (CD2 tk13), yet a more intimate recording would have enhanced the overall impact.

The inclusion of works such as “Wiener Blut” in this collection reflects Strauss’s profound influence on operetta and dance music, yet the arrangement’s reliance on pastiche may leave purists wanting more substantial material. Notably, while this recording captures the essence of the Strauss tradition, it does not quite match the finesse found in more recent interpretations, such as André Rieu’s live performances, which exude a vibrant energy and clarity that this EMI reissue lacks.

The nuanced arrangements and moments of sheer musical joy are occasionally overshadowed by technical shortcomings and a lack of contextual clarity. Despite these limitations, the charm of Strauss’s music endures, and this recording remains a nostalgic nod to a beloved repertoire. The balance of orchestral and vocal elements, coupled with the historical significance of the work, offers a worthwhile listening experience, albeit one that might have benefited from a more attentive engineering process.