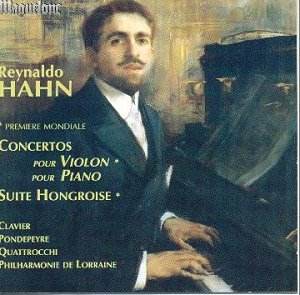

Composer: Reynaldo Hahn

Composer: Reynaldo Hahn

Works: Violin Concerto, Piano Concerto, Suite Hongroise

Performers: Denis Clavier (violin), Angéline Pondepeyre (piano), Philharmonie de Lorraine/Fernand Quattrocchi

Recording: Recorded in Metz, France in 1997

Label: Maguelone MAG 111.106

Reynaldo Hahn, a composer whose artistry flourished in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, often finds his most significant contributions overshadowed by his illustrious contemporaries. This collection, featuring his Violin Concerto, Piano Concerto, and the Suite Hongroise, presents a compelling case for Hahn’s reappraisal. Each work encapsulates the melodic richness and harmonic warmth characteristic of the ‘Belle Époque,’ a period that celebrated sentimentality and lush orchestration. The recordings—particularly of the Violin Concerto and Suite Hongroise, both receiving their premiere recordings here—offer a rare glimpse into Hahn’s vibrant musical language, marked by a delightful blend of nostalgia and lyricism.

The Piano Concerto, composed in 1930, opens with the movement titled “Improvisation: modéré,” establishing an intimate atmosphere akin to a devotional meditation. Angéline Pondepeyre’s interpretation is thoughtful, evoking a sense of rustic charm that aligns well with the work’s French provincial influences. The second subject, reminiscent of Schumann, underscores an effective contrast between introspective moments and robust, dance-like passages. This duality is further accentuated in the central “Dance: vif,” which sparkles with wit, echoing the playful spirit of Saint-Saëns and hinting at the insouciance found in Poulenc’s works. The final triptych movement showcases Hahn’s structural ingenuity, moving fluidly from the haunting “Rêverie” to the exuberant “Toccata,” culminating in a dignified return to the opening material. While Pondepeyre’s performance is commendable, comparisons with Stephen Coombes’ more buoyant interpretation on Hyperion reveal a slight lack of lightness in her execution.

Denis Clavier’s performance in the Violin Concerto, on the other hand, shines with confidence and poetic flair. The opening movement, marked “Décidé,” strikes a balance between rhythmic vigor and lyrical beauty, invoking the opulence of Korngold while remaining distinctly Hahn. Clavier’s phrasing is sweetly expressive, capturing the essence of Hahn’s melodic inventiveness. The central movement, “Chant d’amour,” subtitled “Souvenir de Tunis,” transports listeners to a place infused with the languid heat of North Africa, characterized by a sensuousness that is both inviting and intoxicating. In this movement, Clavier’s ability to evoke emotional depth is particularly notable, as his interpretations draw upon the lush harmonies that Hahn so masterfully crafted. The finale, “Lent – Vif et léger,” starts delicately, preserving the mood of the slow movement before accelerating into a lively dance. The live recording captures the vitality of the performance, though some occasional orchestral imbalances detract from the overall clarity.

The Suite Hongroise, despite its relative obscurity, emerges as a charming work that showcases Hahn’s melodic gift. The first movement, “Parade,” brims with rhythmic zest, blending Slavic and Scottish dance influences into a delightful tapestry. The second movement, “Three Images de la Reine de Hongrie,” encapsulates deep romantic yearning, with its contrasting agitated section providing an effective emotional lift. The concluding “Chants et Danses” encapsulates the suite’s spirit, wrapping the listener in a lively conclusion that encapsulates the joyous nature of the preceding movements. This work’s premiere recording allows listeners to experience Hahn’s delightful craftsmanship in a fresh light, highlighting the engaging rhythms and vibrant melodies that define his style.

This album is a significant addition to the catalog of 20th-century music, offering a rare opportunity to engage with Hahn’s lesser-known orchestral works. The recording quality is commendable, with the orchestral textures clearly delineated, allowing for an appreciation of the intricate interplay between the soloists and the Philharmonie de Lorraine under Fernand Quattrocchi’s direction. The warmth and depth of the sound capture the essence of Hahn’s Romanticism, making this collection an essential listening experience for those intrigued by the musical landscape of his era. The performances, while occasionally eclipsed by other notable interpretations, possess a charm and sincerity that firmly establish Hahn’s place in the pantheon of Romantic composers.